The remarkable fate of this Ukrainian museum has touched many people around the world, making the exhibition possible. As often happens, personal commitment, genuine enthusiasm, and a desire to make changes for the better are the driving forces behind this endeavor.

We spoke with Vera Orlovska, a Ukrainian researcher who, since the beginning of the full-scale war, immersed herself in the world of Ukrainian wartime museums, learned about the fate of the Luhansk Regional Ethnographic Museum, and became inspired by the museum's staff, thanks to whom it exists in its new incarnation. Then there were fantastic individuals around her and a lot of meticulous and inspired work to ensure that the history of this museum, which is crucial for understanding contemporary Ukraine, could be heard within the walls of the exhibition hall at the University of Geneva. We are confident that Vera's story will inspire you just as it has inspired us.

What was your academic background in Ukraine before you came to Geneva and started working at the university?

I studied at the Ivan Franko Lviv National University, majoring in English and German language and literature. After graduating, I worked for a while and then decided to pursue a second master's degree in Germany in the field of "World Heritage Studies." It's an educational program certified by UNESCO and offered at several universities worldwide. I completed my studies in 2016, and since then, I have been professionally involved in various projects related to UNESCO World Heritage or cultural and natural heritage.

After finishing my master's degree, I wrote my thesis on the preservation of transboundary natural reserves. These are areas with natural value that cross political borders between countries, and I explored how these countries can cooperate in preserving them. I worked on this until 2022.

In 2022, I was in Lviv, working remotely with German colleagues and with a Lviv-based company that organized educational tours for children.

Through my academic work, I met many people, one of whom was Dr. Peter Larsen from the University of Geneva. After the start of the full-scale war and several months had passed, he offered me the opportunity to continue my research in Geneva as part of the Scholars at Risk program at the university.

So, you already had a reputation as a researcher, and you were known, which is why you were invited?

So, you already had a reputation as a researcher, and you were known, which is why you were invited?

Yes, that's correct. I've been here since June 2022 and work at the Research Institute for Environmental Governance and Territorial Development (GEDT).

What were you working on when you were in Ukraine?

I was working on the inclusion of the Hin Nam No natural reserve, located between Laos and Vietnam, in the UNESCO World Heritage List. It was quite a complex endeavor, given the process of globalization.

Wow, that sounds challenging. Did you continue that work even after coming to Geneva?

No, I'm not continuing that work at the moment.

Could you please tell us more about the educational program you participated in Ukraine?

The program was organized by "Divis Shirshe," a company based in Lviv that helps young people aspiring to study at Austrian universities achieve their goals. I managed their career orientation programs, where we assisted teenagers in choosing their academic paths and gaining a better understanding of them. We went on short trips together to the Carpathian Mountains and Austria, where future students studied the German language, explored questions of cultural identity, and learned the basics of project management.

After the start of the full-scale war, the ALIPH Foundation contacted me. Their mission is focused on preserving cultural heritage in areas at risk. They became very active in Ukraine during the conflict, assisting Ukrainian museums, archives, and libraries. This assistance included funding for the conservation of damaged buildings, evacuation of salvageable collections, proper packing of museum items, digitization of collections and artifacts, and providing scholarships to museum professionals. I joined their efforts in helping them.

Then I was offered a position at the University of Geneva. It turned out that both the foundation and the university I had been collaborating with were located in Geneva.

Can you tell us more about what you did for museums in Ukraine in collaboration with the ALIPH Foundation?

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the Foundation has supported over 200 institutions in Ukraine. Part of my work was to establish connections with Ukrainian museums, not only with the central ones but also with smaller regional ones. Building contacts with the teams of Ukrainian museums, libraries, and archives required significant effort, especially since many Ukrainian cultural institutions had limited experience in international cooperation, even during peacetime. Often, our grant recipients needed substantial support in preparing grant applications and communicating with foreign donors. Institutions throughout Ukraine, from Lviv to Luhansk and Donetsk, received assistance from the ALIPH Foundation.

It was through my work with the ALIPH Foundation that I got to know the team from the relocated Luhansk Regional Ethnographic Museum. Unfortunately, many Ukrainian cultural institutions are now under Russian occupation, and their collections and archives are either stolen, destroyed, or used as tools of propaganda. However, some employees of these occupied museums manage to leave for safer territories. These individuals continue their work in new locations despite the challenges they face.

But how do they manage to do it?

But how do they manage to do it?

That's a big question. Even before 2022, Ukrainian cultural institutions were quite vulnerable. With the new destructive wave of Russian aggression, museums in the territories that were occupied in the first weeks of the full-scale invasion quickly lost access to their buildings and collections. However, Ukrainian museum professionals were not deterred. They find solutions even in the most challenging situations and continue to represent their cities' museums, even when they are hundreds of kilometers away, like the Museum of Luhansk in Lviv, for example.

Today, working in a museum in Ukraine is not easy. Being a Ukrainian museum professional is a constant struggle for the opportunity to continue working. Even for museums that remain in their buildings with their collections, state support is extremely limited. Staff reductions and low salaries are common. Nevertheless, the mutual support within the Ukrainian museum community is impressive. For example, the relocated Luhansk Regional Ethnographic Museum found itself in Lviv because its evacuation was supported by the Museum Crisis Centre in Lviv, and a partner institution - “Territory of Terror” Memorial Museum - was prepared to host their colleagues in displacement. They share exhibition space and collaborate on joint projects. This is fascinating and cannot be summarized in a few words.

However, museums like the one in Luhansk face greater challenges in securing support. For instance, if a museum's building is damaged or its collection is at risk, the course of action is more straightforward. But what if there is neither a building nor a collection? In my work, I realized that there are institutions that seem to fall through the cracks of international aid, and something needs to be done about it.

The major war showed that a museum is not just a specialized building where ancient items are stored, and history is told. It holds a non-material value as well because it is about people, understanding and appreciating one's cultural identity, and making sense of the present.

And so, here in Geneva, on the one hand, I did everything I could to bring more clarity to the issue of supporting such museums, and on the other hand, I had contact with the Luhansk Regional Ethnographic Museum and access to exhibition space at the University of Geneva.

And that's how the exhibition came to be...

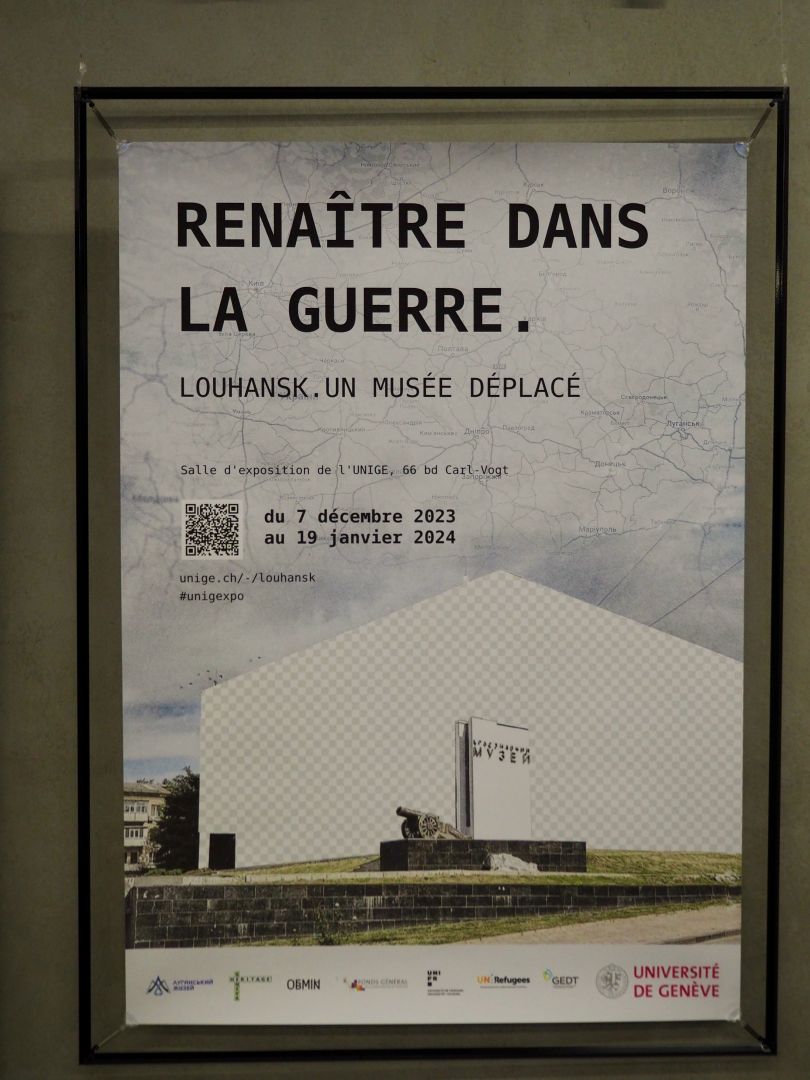

Yes. All of this together contributed to the exhibition being presented here. Initially, in June of this year, it was displayed at the University of Fribourg in the form of a banner exhibition and roundtable discussions. Then it transformed, expanded, and was presented in Geneva.

Did the University immediately support your initiative? How does your environment perceive projects related to Ukraine?

Did the University immediately support your initiative? How does your environment perceive projects related to Ukraine?

My environment has been fantastic! Both my team and the director of the Luhansk Museum, Olesia Milovanova, provided strong support. This was crucial because preparing the exhibition was a significant undertaking. We had to figure out how to convey all this information to the local audience, write, proofread, and edit texts to make them understandable. At the same time, it was important for us not to tell the visitors what to think about what we were telling and showing them. This is exactly what Russian propaganda does, and it couldn't be our approach. Our goal was to present the experience of the Luhansk Museum in a comprehensive, reasoned, open manner and allow visitors to draw their own conclusions. This turned out to be quite challenging.

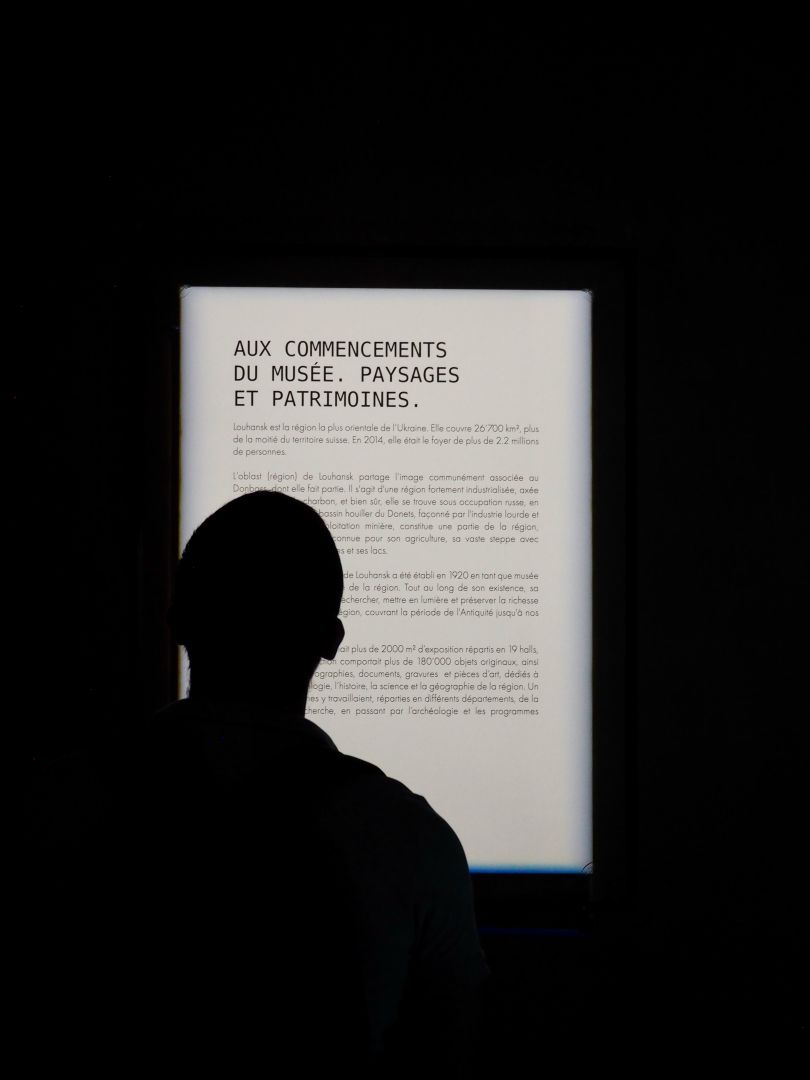

I should note that we did not center the exhibition around war, destruction, or pain. It is not about victimizing Ukrainian culture.

And what is it about?

It's about a team of very powerful, cool people who, despite everything, continue to do their job excellently. It's about how their work is crucial because Ukraine is fighting for its cultural identity. Our exhibition is about how museum professionals stand up for themselves, for their Luhansk region, and their culture. They preserve their professional dignity, grow, and work to come out of this war stronger. While working on the exhibition and communicating with our international colleagues, we often said that being a Ukrainian museum today is always preparing for the end of the world but also having some plans for afterward. For the Luhansk Museum, this "mode" started back in 2014.

It's a very symbolic situation.

It's a very symbolic situation.

Yes, it's essential to remember that the events of 2022 are not new because this history has been ongoing since at least 2014. The exhibition shows how this unfolds through the experience of just one museum.

After the events of 2014, the Luhansk Museum was restored in territory controlled by Ukraine, in Starobilsk. The museum in Luhansk also remained but became the People's Museum of the so-called "LNR" and serves entirely different purposes, telling completely different stories and emphasizing different aspects, despite having the same museum collections.

You could make a movie about this...

This "split" of one museum also became a significant focus of the exhibition. We represented it as a kind of "passage." Walking through it, on one side, the visitor sees the realities of the occupied museum in Luhansk. Examples of recent exhibitions, excerpts from the current leadership of the museum, directives for museums in the newly annexed territories from the Russian government, and more. On the other side, the re-establishment of the "relocated" museum in Starobilsk. Museum expeditions and the collection of new ethnographic items, documentation of the ATO/OOS events, decommunization efforts, and so on. Walking through this space, the visitor can witness two parallel realities.

We put a lot of work into figuring out what and how to present in the exhibition. This was done through numerous discussions among all partners, both Ukrainian and Swiss. Many things cannot be disclosed for very obvious reasons, and we don't do that.

For the exhibition, we involved our Ukrainian experts who were also displaced. For instance, the fantastic designer Alexander Bukreev, who is originally from Luhansk, and scenographer-architects Igor Goma and Alexei Bykov. It was very valuable to have people who know and live the subject matter working on the exhibition.

To illustrate the events in Luhansk in 2013-2014, which preceded the Russian occupation of the city, we contacted photographer Alexander Volchansky, who shared his unique photo archive of the events of the Luhansk Maidan.

We also reached out to poet Serhiy Zhadan, who allowed us to complement the exhibition with two of his poems, illustrating the beginning of the Russian onslaught. By the way, Serhiy is also originally from Luhansk, from Starobilsk.

Starobilsk is currently also occupied, and the museum had to relocate again.

Starobilsk is currently also occupied, and the museum had to relocate again.

Yes, Starobilsk was occupied in the first days of March 2022. The Luhansk museum eventually found itself in Lviv, where it is hosted by the “Territory of Terror” Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes." Currently, in Lviv, a new collection for the museum is being formed from items donated by people from Luhansk. They are giving the relocated museum their items with their stories, and some of these items, the director, Olesia Milovanova, brought to our exhibition.

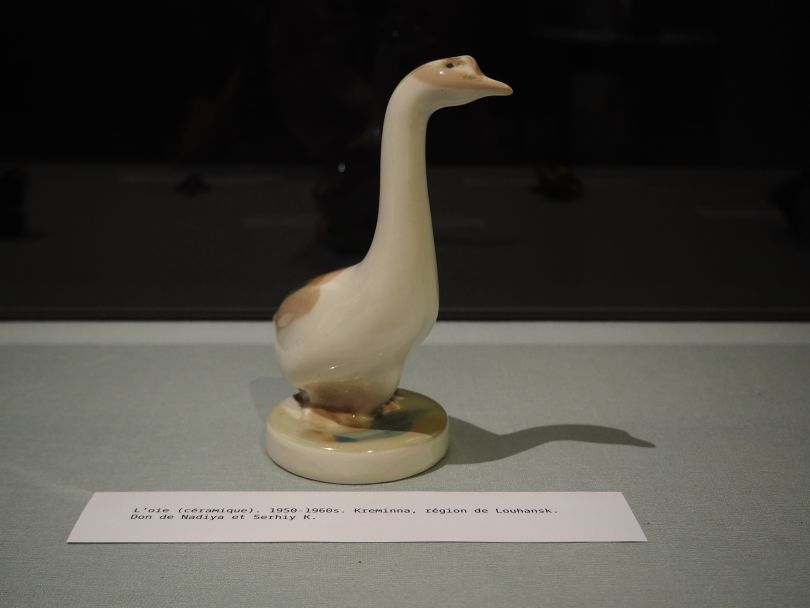

For example, there's a clay figurine of a goose from Kremenna. It survived in the ruined house of a family who took it with them during the evacuation and later gave it to the museum. When you look at it, it seems like an ordinary ceramic goose, but its value has changed significantly.

There's also a peculiar collection of old vinyl records. There are albums of a young Sofia Rotaru and "Pisniary." These records belonged to a family where the grandmother was a music teacher. They had a record player, and during holidays or family evenings, the family listened to her collection. When they were leaving, they decided that it was crucial to take it with them. But later, they donated the records to the museum. In our hall, there is a so-called "sound soul" hanging from the ceiling, and when you stand under it, music starts playing. It feels like the music is coming from headphones, and in the headphones, you hear Ivasyuk.

When Ukrainians visit the exhibition, I can recognize them immediately because they stand under that "sound soul" and repeat the words, "Love only blooms once"... It's very powerful.

How do the Swiss react?

How do the Swiss react?

The staff in the exhibition hall say that there is a lot of interest in this exhibition, even compared to others. People come not only during guided tours but also on their own.

We also placed excerpts from Zhadan's poems in French translation on the display windows in the exhibition hall, similar to what they do in Lviv on the walls of buildings. This also works well and invites people to enter.

Interestingly, at the opening, there were about 70% foreigners and 30% Ukrainians.

That's a very good indicator.

Yes, it's not just a Ukrainian event where only the Ukrainian community gets involved. It has a broader format.

People also often ask how they can help Ukrainian museums like these.

We have a museum book about the exhibition, and many people are interested in whether they can purchase it. They also say that the events of 2014 have long disappeared from the media space, and it's good that this exhibition reminds people of those events.

What other interesting exhibits are there at the exhibition?

We illustrate the events of 2014 in Luhansk with photographs by Alexander Volchansky, who documented everything that happened in Luhansk at that time. It's a massive photo archive. For example, in one of the photos we displayed, you can see a Ukrainian rally - for Ukraine, the Maidan - and there are very different people there. But when it comes to the rally under the flags of the Russian Empire, where people are saying, "We are Russians, God is with us," it's only men of a certain age and build. This immediately sparks reflections. Visitors themselves ask, "Did you notice this?" And I say that I did, and I'm very glad they noticed it too.

Your exhibition will run until January 19th.

Your exhibition will run until January 19th.

Yes, it will be in the exhibition hall of the University of Geneva until January 19th for sure.

What are your future plans?

Currently, at least seven Ukrainian museums have expressed interest in hosting the exhibition. So we are working to find the necessary financial support for it to travel within Ukraine. We are also exploring the possibility of taking it to other countries. However, as of today, nothing has been confirmed yet.

Who supported the financing of the exhibition in Geneva?

This is also a very important story because several organizations supported the exhibition. This includes the Geneva Heritage Lab, initiated by Dr. Peter Larsen, with whom I have the pleasure of working. Also, the team from the Faculty of Contemporary History at the University of Fribourg. The International Platform for Supporting Ukrainian Museums "Obmin" and the German Gerda Henkel Foundation helped provide scholarships for museum professionals to do their work. They also assisted with some equipment for the museum because people evacuated, at best, only with their phones, and you need at least computers to work. Undoubtedly, the General Fund of the University of Geneva, the Scholars at Risk program under which I am currently here, and the Integration Department of the University of Geneva (Délégation intégration de l’UINGE) provided significant support. The institute where I work, the Institute for Environmental Governance and Territorial Development (GEDT), also greatly supported our exhibition project. The exhibition space at the University of Geneva - SEU - Salle d'exposition de l'UNIGE - supported us at every step, which is incredibly valuable.

What a powerful example of European unity!

This became possible because everyone worked together. It's amazing, and a tremendous amount of work was done.

What do you think is the most important aspect of the work of the Luhansk Museum now? Preserving memories of the true museum?

In my opinion, Ukrainian museums should not just live on memories. They are primarily spaces for understanding the present, their own identity, and their place in the world. Museum professionals must document what is happening in the occupied territories and conduct research. Who else will sit so diligently and monitor what the occupied museum is doing? I was involved in this to some extent when we were preparing the exhibition. But Luhansk museum professionals do this systematically because it's their museum. And after victory and de-occupation, they will be the ones to return there to start the restoration.

It's also important that they remain a focal point for Luhansk's identity, no matter where they are. They can be seen and heard, and they continue to work despite all the difficulties.

Here, it's also important that all these documented facts and research are not limited to narrow communities. This information should reach a wider audience.

There was a report about our exhibition on Swiss radio and television, and there were publications in central Geneva newspapers. People often come because they read about it in the newspapers. But we only communicate with the media about the exhibition. Overall, you are right; this topic mustn't remain confined within museum walls.

And only through the efforts of scholars... Let's get back to your research. What are you currently working on?

My main area of work here is the cultural and natural heritage of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. This zone has existed since 1986, and it's a long period, so we can track what has been happening there. Chornobyl Polissya is a unique ethno-cultural space that has remained hidden behind the curtain of the Chornobyl disaster. While researching this topic, I see that the preservation of the cultural heritage of Chornobyl Polissya is happening, and even entire expert expeditions have been organized to the Zone. However, the public knows very little about this work. Unfortunately, in Ukraine today, a significant number of exclusion zones have formed, and it might be worth considering the experience of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone – to analyze what could be done better, to organize more efficiently. By the way, we may be one of the few countries that have a separate "State Scientific Center for the Protection of Cultural Heritage from Technogenic Disasters." Their representatives were invited to Japan to talk about their work in the Chornobyl Zone, but in Ukraine, very few people know about them.

Once again, we come to the point that such things need to be shared with the public. Your exhibition is an example of where to start. So, we invite our readers to visit it.

Thank you for such an informative and engaging conversation.

The exhibition in Geneva by the Luhansk Local History Museum "Rebirth in Times of War. Luhansk. Displaced Museum".

When: December 7th to January 19th, 2023

Visiting hours:

Monday-Friday: 7:30 AM - 7:00 PM

Sunday: 2:00 PM - 5:00 PM

Location: UNIGE Exhibition Hall: SEU - Salle d'exposition de l'UNIGE, at 66 Boulevard Carl-Vogt

The poems by Zhadan used in the exhibition are: "Street" and "Take Only the Most Important."