Alla was a prominent figure in the Sixtiers Movement. This term later became associated with the young artists of the 1960s, a period known as the «Thaw» following Stalin's death. However, it was short-lived. When the temporary relaxation ended, the Sixtiers faced repression: some were sentenced to prison terms or died. Poet Vasyl Symonenko died after being beaten in a police station, Vasyl Stus perished in prison, and Alla Horska was found murdered with an axe in her father-in-law's cellar.

During those years, the Soviet regime no longer resorted to mass executions as during the Stalin era, but employed different methods of suppression.

Horska was perhaps one of the most vibrant representatives of the «Shchopta» the Ukrainian talented youth, as described by Vasyl Stus in his poem dedicated to her memory («Flare up, my soul. Flare up, don't cry...»). She was called the «Soul» of the community because she helped everyone — those condemned, tortured, exhausted. She also boldly spoke out against the government's wrongdoings, challenged the KGB during interrogations, and even mocked the spies who followed her like shadows in her final years. They also called her «the heart of an eagle»... She was only 41 when she died. But she accomplished a lot.

Golden girl from the «Soviet elite» family

Alla Horska was born on September 18, 1929, in Yalta. Her father, Oleksandr Horskyi, was the director of various film studios — first in Yalta, then in Leningrad, Alma-Ata, and later in Kyiv.

Her mother, Olena, initially worked as a nanny in childcare institutions. After moving to Leningrad, she became a costume designer and never abandoned this profession. So the girl had access to the artistic circles of the Soviet era, which helped her find herself in her art.

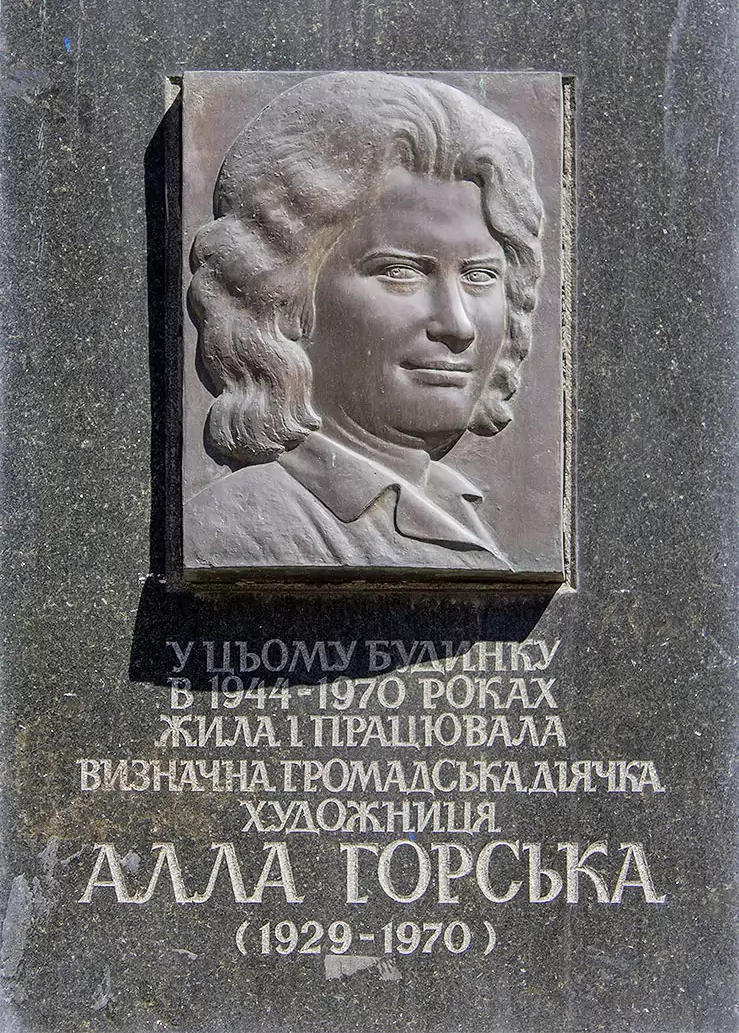

At the age of 11-12, she and her mother were in blockaded Leningrad. Her father was absent, having left for Mongolia for a film shoot and was unable to return. After the blockade was lifted, the family reunited in Alma-Ata, and in 1943 they moved to Kyiv, where her father was offered the position of director at the Kyiv Film Studio. He received a three-room apartment in the city center, at 25 Tereshchenkivska Street (then it was called Repina). A memorial plaque dedicated to the artist can now be seen on the building.

The memorial plaque, 25 Tereshchenkivska Street

Later, this apartment became a cult place for all Sixtiers — there were «apartment gatherings», artists gathered, friends and acquaintances of Alla found refuge there. Even unknown artists found shelter there when they were in trouble.

Years of Education

Alla enrolled in the Taras Shevchenko Art High School. It is noteworthy that at the school named after the most prominent Ukrainian poet, the person who shaped the Ukrainian literary language, Alla was exempted from studying Ukrainian. In those years, all urban Ukrainians had such an opportunity — not to study their native language, while Russian was mandatory. This was one of the methods of Russification of Ukrainians.

Compared to all the other Soviet children, Alla looked like a «major» (rich kid). Her father's service car brought her to school every day, and the driver brought her sandwiches for lunch. This could have hindered her integration into the team, but her sincere and gentle nature helped her to fit in.

«A few months after the start of her studies, Alla became a leader. She was tall, gray-eyed, a smart girl, gentle, kind, sociable — she brought everyone together», wrote her school friend Halyna Zubchenko in the book «The Red Shadow of the Viburnum».

After graduating from school with a gold medal, the girl entered the painting department of the Kyiv Art Institute.

Her works were immediately exhibited at all-Union exhibitions, and it seemed that Alla was destined for a brilliant career. But then she suddenly became passionate about Ukrainian identity.

Friends say that the young artist began to feel ashamed of not knowing the language of her ancestors. And after visiting the Ivan Honchar Museum of National Folk Culture, where she was able to connect with her national roots, the young artist was struck by a new sense of belonging. Inspired by this experience, she decided to make a change and began studying the Ukrainian language and immersing herself in Ukrainian identity in all its forms. This began to reflect in her work. Ukrainianness began to sprout in the artist, despite the dominant style of «socialist realism» at the time, which was defined by the regime as the only possible one.

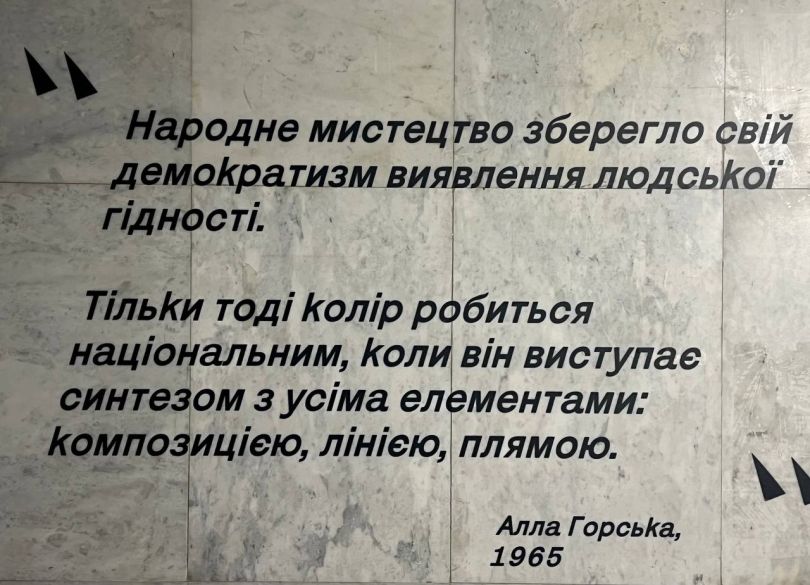

«Folk art has retained its democratic character of expressing human dignity. Only then a color becomes national when it acts as a synthesis with all the elements: composition, line, spot».

Marriage and Birth of a Sin

While studying at the institute, Alla Horska met Viktor Zaretskyi, her future husband. The lovers worked in the same studio, made artistic trips around Ukraine, and became interested in monumental art together. Viktor also contributed to his wife's growth as a Ukrainian artist.

In 1954, the couple welcomed their son, Oleksiy.

«Self-portrait with son», 1960.

In his mature years, Oleksiy would become a consistent collector and guardian of his mother's memory, and now his granddaughter, the artist Olena Zaretska, continues his work and contributes to events aimed at restoring the memory of Alla Horska and her achievements.

Creative Youth Club

From 1961 to 1965, Horska, along with Viktor Zaretsky, Vasyl Stus, Vasyl Symonenko, Les Tanyuk, and Ivan Svitlychny, became an organizer and active member of the Creative Youth Club «Suchasnyk» which became the center of Ukrainian national life in Kyiv. It was from there that the Sixtiers movement began.

Self-portrait, 1958.

Her friend Serhiy Bilokin described Alla as follows: «A tall, powerful blonde. Smiling, sincere eyes from under a sheaf of luxurious golden hair. (...) Alla lived among us, but it felt like she belonged to a different breed of people, a titanic breed, the crest of the raging Ukrainian element. It was impossible to stop Alla».

The regime tried to intimidate her and take away her job. But she did not obey.

The destroyed stained glass window and the first professional blow

«I will exalt those little silent slaves, I will stand guard over them with my word!» — this quote by Taras Shevchenko became the main message of the majestic stained-glass window that the Soviet regime commissioned to decorate the lobby of the red building of Kyiv University on the occasion of his 150th birthday. It was created by a group of artists: Alla Horska, Opanas Zalyvakha, Lyudmila Semykina, Halyna Sevruk, and Halyna Zubchenko.

In the center of the composition, the artists depicted Taras Shevchenko, who hugs Mother Ukraine with one hand and seems to be stopping the offenders with the other. After seeing the model, the party leadership was shocked, called the work formalistically hostile, and the fate of the work of art was determined. There was too much Ukrainianness in it, and the Prophet's words sounded like a threat to anyone who offended Ukraine. The model of the stained glass window was smashed to pieces the next day after it was installed. It was called hooliganism in art, and the artists were expelled from the Union of Artists.

«Shevchenko. Mother» stained glass window for Kyiv University, 1964.

Then the KGB organized a wiretap in Alla's apartment. Later, persecution became commonplace.

Bykivnia

The most powerful act of Alla and her friends Vasyl Symonenko and Les Tanyuk was their trip to Bykivnia, a mass grave site for Ukrainians shot by the NKVD in the 1930s, now known outside Ukraine. What they saw impressed everyone. Les Tanyuk recalls how Alla sobbed as she stepped aside...

The most terrifying episode of this event was when the artists saw children playing football on the lawn... with a human skull with a bullet hole in it.

Upon returning from Bykivnia, the friends, shocked to the core, wrote an official appeal to the Kyiv authorities demanding that they investigate the incident, begin identifying the dead, and organize the burial. But there was no response.

A mass grave, Bykivnia

But something else began-the first arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals after Stalin's death. Many of the artist's friends were imprisoned, including the artist Opanas Zalyvakha, one of the authors of the stained-glass window «Shevchenko. Mother», who was sentenced to five years in the camps. When the arrests began, Alla Horska sent a statement to the prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR, protesting against human rights violations.

And then she went to Mordovia to visit Oleksa, even though she knew that she would not be allowed to see him. But the prisoners saw Alla from afar: «We recognized her by her height and her famous long fur coat. She looked as if the princess had arrived at her estate and could not enter because she had lost her keys (!). Alla was full of despair and discontent. Both I and our community were warmed by the mere sight of such a tall figure from our Golden-Domed Kyiv», Zalyvakha wrote in his book «The Red Shadow of the Viburnum».

A job that allows you to cope

All this time, she continued to work with inspiration: many of the grandiose art projects she created with other monumentalists were realized in the cities of Donbas. Those that are now occupied or even destroyed.

In particular, Alla Horska's and Viktor Zaretskyi's mosaics «Tree of Life» and «Boreviter» were located in Mariupol. In 2022, they were virtually destroyed by Russians, who tried to conquer the unbreakable Ukrainian city and eventually occupied the ruins.

These works were experimental, as the artists used non-standard materials: slagged steel and metal; in «Tree of Life» there were fragments of sheet aluminum, and in «Boreviter» stainless spoons.

«Boreviter»

«Boreviter». Destroyed.

In Donetsk, which has been occupied for 10 years, the artists created a series of unique mosaics by Alla and her colleagues. Their fate is currently unknown.

Video by Radio Freedom, October 8, 2013.

But in Kyiv, only one monumental work by Alla Horska, Viktor Zaretsky, and Borys Plaksiy, Wind, has survived. It is an abstract mosaic panel based on folk art.

Mosaic «Wind», Kyiv

Alla also creates self-portraits, portraits of many of her like-minded friends (in tempera, gouache, linocut), and as part of her collaboration with the theater experimental studio founded by her friend, director Les Tanyuk, she designs sets and costume sketches for the plays «Mother Courage and Her Children» by Brecht, «A Knife in the Sun» by Drach, and «The Sublime sonata» by Kulish. He is working on the design of the plays «Truth and Offense» by Stelmakh and «That’s how Guska Died» by Kulish, which were being prepared for performances in state theaters. Both performances were banned, the last one was removed from the stage right on the day of the premiere.

Sketch for the play «A Knife in the Sun» by Ivan Drach

The pressure intensifies

In the second half of the 1960s, Horska was repeatedly interrogated by the KGB, where she behaved independently and defiantly.

«She crossed the threshold of fear-she was no longer afraid of anything or anyone. And this is very undesirable, dangerous for those in power», says artist Halyna Sevruk about her friend.

Despite all this pressure, Alla continued her human rights activism. In 1968, she signed a famous letter of protest signed by 139 scientists and cultural figures to the leadership of the USSR against the persecution, arrests, and trials of dissidents. Repressions against the signatories began almost immediately. Horska was expelled from the Union of Artists for the second time.

Under the Soviet regime, expulsion from the Union was tantamount to professional death. Without membership, it was difficult for artists to buy even paints, and of course, no one exhibited them, no one gave them government contracts, which meant that there were practically no orders at all.

But she still worked, sometimes incognito, as a member of a group of monumentalists.

The artist gave part of the money she earned to the families of political prisoners or those returning from the camps.

Death

On November 28, 1970, Alla Horska went to Vasylkiv to visit her father-in-law Ivan Zaretskyi. She did not return that evening. Her husband Viktor Zaretskyi went to Vasylkiv the next day, but found his father's house locked. Despite the family's alarm, the police did not agree to open the house by breaking down the door.

On November 29, the body of Ivan Zaretsky with his head cut off was found on the tracks near the Fastiv-2 railway station. On December 2, the police finally entered the house and found the body of Alla Gorska in the cellar, killed from behind with an axe to the head.

The investigation concluded that the father-in-law (Ivan Zaretsky) had killed his daughter-in-law Alla Horska out of personal animosity and then committed suicide. This was immediately rejected by everyone — the father-in-law was a frail elderly man, and the murder was «professional», as one of the investigators noted. In addition, there is evidence that before her death, Alla met with a stranger whom she was talking to in Shevchenko Park in Kyiv. The case was quickly closed.

Everyone in the dissident community and in the family was convinced that it was a political murder.

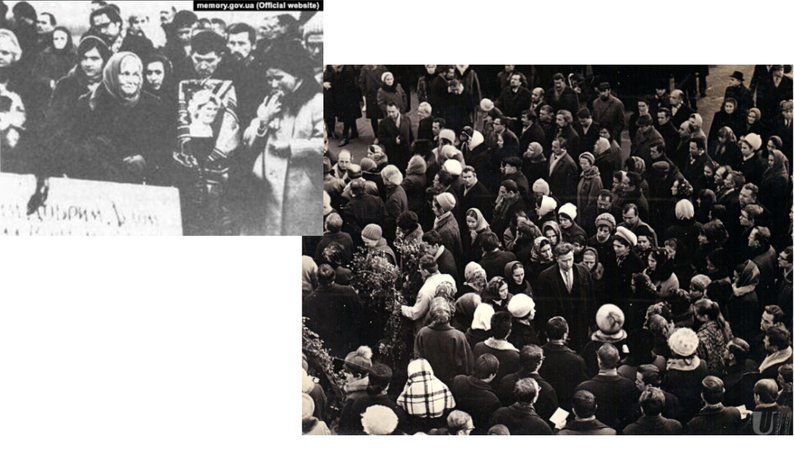

Alla Horska's funeral in Kyiv on December 7, 1970, turned into a protest rally against the communist regime.

Vasyl Stus was the first to publicly call Alla Horska's death a murder.

Left: Vasyl Stus holding Alla's portrait at her funeral. On the right are Alla's admirers, who came to pay their last respects.

Horska's work and personality were silenced until Ukraine gained independence.

Currently, a large exhibition of Alla Horska titled «Boreviter» is taking place in Kyiv, featuring 100 works by the artist.

The exhibition was an event of great importance in wartime Kyiv. The symbolism of her works and her fate fit into the context of our time. Her works are relevant, and her victory and resilience are an example of the true Ukrainian spirit.